Sample translation by Nicky Harman.

Read a sample | Inquire about the rights

Read a sample | Inquire about the rights

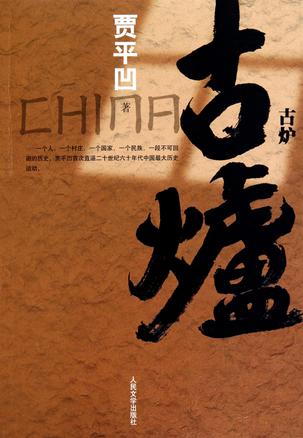

Name in Chinese: Gu Lu 古炉

Publisher: People’s Literature Publishing House, 2012.

Length: 607 pages, about 670,000 Chinese characters. This would translate into between 440,000 and 450,000 English words.

“No previous work has provided such a microscopic view of the fates of ordinary farmers during the Cultural Revolution. Rather than pointing fingers at anyone over the nation’s spiritual catastrophe, Jia seeks to reveal the gradual collapse of moral principles, as people in remote Old Kiln village are swept up in, and away by, political movements. Perhaps even more important is Jia’s ability to look beyond human values and show the insignificance of mankind as it stands before Mother Nature.”

– Liu Jun, China Daily“Old Kiln Village is unlike other novels set during the Cultural Revolution, which focus primarily on political turmoil and brutality; instead, it treats the period as being like any other time in history, when the villagers’ priority is the problems of daily life. In fact, the Communist Party secretary of the village does not even know that such momentous events have begun until some Red Guard youths arrive to make trouble and recruit members. The everydayness of village life and the deeply rooted cultural traditions remain the same, while the political storms come and go. There will, of course, always be restless young men looking for excitement. Hence, the political engagement of the Red Guards is characterized as a release of hormonal pressure. The power of the story lies in the daily negotiations between what the higher authorities want and the villagers’ daily pursuit of survival under poor conditions.”

– Wang Yiyan, Chinese Fiction Writers, 1950-2000

In 1966, the Cultural Revolution erupts in Old Kiln, a remote, poor and backward village, located in a mountainous region of Shaanxi province where the Zhu clan dominate village life. They are rivalled in size only by the subservient Ye clan. The few families with different surnames in the villages, meanwhile, are known as the “outsiders.”

Main characters

Mottlegill is a young boy of about 11 or 12. In a “bad class category” (parents and grandfather fled to Taiwan after 1949) and the target of all the village bullies. Underdeveloped and puny, but quick-witted. Mottlegill occasionally talks with animals, and has a peculiar sensitivity to a certain smell that foretells disaster. Belongs to the Zhu clan.

Grandma Mulberry is Mottlegill’s grandmother and only remaining family. In a “bad class category” (see above), and has spent time in the county prison. A healer and midwife, she makes folk art papercuts in her spare time, but is careful to hide this from the village bureaucrats. Belongs to the Zhu clan.

Cowbell is Mottlegill’s only friend of the same age.

Apricot is Roughshod’s childhood sweetheart. She is the daughter of Full-bowl, the retired production team leader who re-built the kiln, the villagers’ only source of income.

Roughshod is a young man frustrated by the constraints of village life. His parents are dead and he has moved to live in a shed on his own on the main road, where he makes some extra cash mending shoes. The ringleader of the Sledgehammers, the Red Guards faction that comes to dominate the village. Belongs to the Ye clan.

Goodman is a monk who was forced to leave his monastery after 1949, lives alone in the Kiln God Temple. He also works as a healer and shaman, to the disapproval of the local Communist Party officials.

Reader Report

Old Kiln is an immense panorama of a novel, but extremely readable. There are grand themes—the destabilization of a community and its eventual destruction, the effects of violence and treachery and how ordinary people behave under extreme pressure. So much for the new. But some things have not changed: village life is one of grinding, millennial poverty and backwardness, likely to be as alien to western readers as it is to many Chinese readers. The earthy detail, the talk of human and animal ordure, reminds one of a Breughel painting. However, in contrast to the violence and the strangeness, there are plentiful vignettes of ordinary life and intimate relationships; for instance, Grandma Mulberry, Goodman, Apricot and Mottlegill, immediately engage the reader’s sympathy, although other characters are as harsh and abrasive as the landscape they live in.

At the same time, the novel is replete with fantasy: Mottlegill talks to animals and they talk back to him. He smells a smell that portends catastrophe and can eat the taisui without suffering ill effects. (Interestingly, he and the other fey characters—Goodman and Grandma Mulberry—are all on the margins of the political life of the village.) The village characters; almost all have bizarre, uncouth nicknames, though their origin is never explained. Jia has said that they are not traditional but a product of his imagination, and integral to the layers of imagery he builds up in the story. While registered name of Mottlegill, for instance, is Zhu (surname) Ping’an (given name), he is nicknamed after a local mushroom.

The combination of fey, supernatural elements and the political events of the story allow Jia to vary the rhythm of the narrative. Jia takes us from an intimate scene between grandmother and grandson, to political meetings, to vignettes about village farming, to armed struggle, and back to Apricot’s tears as she realizes that her rival has caught scabies and must therefore be having intimate contact with Roughshod. We do not linger too long in any one setting, but move from one to another. The story is richly-textured, mixing the mundane and the apocalyptic. It is peopled with real human beings in all their infinite variety—devious, cruel, generous, funny, brave, and ultimately stoical.

Finally, the denouement, with its execution scenes and the rollcall of the dead, is gripping. It is also abrupt: one day the factions are at each others’ throats, the next day, the army is back in charge and order is restored. This slightly deus ex machina effect underscores the pointlessness of the entire political upheaval. As the novel concludes, there is a feeling of calm after the political storm, but we are also left with a lingering feeling of waste, of unnecessary suffering.

As with Jia’s other novels, the narrative technique is particularly appealing in this book. Jia introduces key information in an almost casual way. This somehow gives the impression that one is immersed in the village oneself. For instance, there is no single moment at which it is stated that Apricot is pregnant. The reader simply observes her growing bigger and her clothes tighter. In this sense, there is something Hardy-esque about this village and the women in it.

Another example: towards the end of the novel, it is stated quite casually that Grandma Mulberry has served time in the county jail, presumably because of her son, daughter-in-law and husband. This is shocking because by this time, we are thoroughly in sympathy with this gentle woman, whose character is reportedly based on Jia’s own mother.

Finally, one has to consider in a book this length whether it could or indeed should be shortened. There are many arguments that might be made for streamlining or pruning some of the political struggle and battle scenes. However, this would not significantly affect the overall length of the novel, since important details are included on every page. Some of the most important bits of information about the characters are slipped in almost casually, for instance Grandma’s spell in jail, adding to the reader’s overall sense of immersion.