To be published by AmazonCrossing in 2020, co-translated by Dylan Levi King and Nicky Harman.

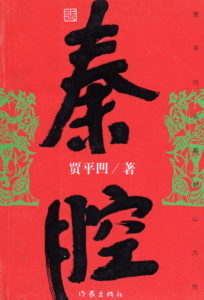

Name in Chinese: Qin Qiang 秦腔

Publisher: The Writers Publishing House, 2005

Awards: Dream of Red Chamber Award (2006), Mao Dun Literature Prize (2008)

“The monumental novel Shaanxi Opera details the lives of the residents of the village of Qingfengjie (Clear Wind Town) in the 1990s and early 2000s from the viewpoint of Yinsheng, a young man with mental problems and a connection to supernatural forces. Two families, interrelated by marriage, have dominated the politics of the village for generations: the Bais had the upper hand before the Communist takeover, but the Xias are in control now. An important aspect of village life is Shaanxi’s local opera, Qinqiang. Xia Tianzhi has an encyclopedic knowledge of the opera; his daughter-in-law, Bai Xue, the village beauty, is the star singer in Qinqiang. Music from Qinqiang always hovers over the village, as Xia Tianzhi plays it on a loudspeaker. The villagers sing a lyric or two when certain situations arise and use lines from the play catchphrases. But the decline of Qinqiang is inevitable in the age of globalization and mass popular culture. When the county Qinqiang troupe loses its funding, the performers are forced to become entertainers at weddings and funerals. Likewise, village life is becoming unsustainable. Most of the households are in debt, and there is a shortage of food. Work on the land no longer attracts the younger generation, and they leave one by one to find work in the city.”

– Wang Yiyan, Chinese Fiction Writers, 1950-2000“Shaanxi Opera is full of cod-classical language set down beside scatological local dialect expressions, beautiful lyrical passages and bone hard descriptions of the filth of public toilets and dirt floor shacks. Jia Pingwa’s countryside is full of sex, shit and violence, expressed with a literary form that’s a hybrid of dirty jokes and classical poetry.”

– Dylan Levi King, Paper Republic

Set in Jia Pingwa’s native countryside, Shaanxi Opera takes place in a time of rural reform. It charts the fortunes of two families — the Bai and Xia families — in the village of Qingfengjie. The Bai family has fallen from their status as the most powerful family in the region and been replaced by the Xia family, who enthusiastically joined the Party. The narrator is Zhang Yinsheng, a member of neither family, who has fallen in love with Bai Xue. Bai Xue is the most beautiful girl in the village and her marriage to a sophisticated, urbanized son of the Xia family might unite the two great families of the village.

The title refers to a local style of opera, known in Chinese as ‘qinqiang,’ or ‘Qin dialect’ opera—so named because the borders of modern day Shaanxi are roughly analogous with those of the ancient state of Qin, founded in the 9th century BC. More than being a book just about a regional style of opera, however, Jia uses the decline of Shaanxi opera to represent the decline folk customs of the rural people of Shaanxi.

Main Characters

Zhang Yinsheng is the narrator and main character. After his father’s death he becomes prone to fits of madness and hysteria. Obsessed with Bai Xue.

Bai Xue is a Shaanxi Opera singer, born in Qingfengjie, marries but eventually divorces Xia Feng, scholar of the Xia family who makes good in the county seat. Comes from a family of former landlords who lost everything following the 1949 revolution.

Xia Feng is a semi-famous author of essays and eldest son of Xia Tianzhi, older brother to Xia Yu, husband to Bai Xue. Works in town, so the villagers all look up to him for his urban sophistication.

Xia Tianren is the oldest of the four Xia brothers, famous for killing a tiger with a single blow, accidentally blown up while building a reservoir before the book begins. Father of Xia Junting.

Xia Tianyi is the second Xia brother, former land reform representative, village head, and father of five sons: Xia Qingjin, Xia Qingyu, Xia Qingman, Xia Qingtang, and Xia Xiaxia. Dies towards the end of the book pursuing his quixotic life-long quest to reclaim the wasteland at Qiligou after enlisting the help of Yinsheng and the Mute.

Xia Tianli is the third Xia brother, a retired clerk, in poor health and famously stingy. Father of Xia Leiqing.

Xia Tianzhi is the youngest of the four Xia brothers, father of Xia Feng and Xia Yu.

Xia Junting is the current village head, promoted to Party Secretary early in the novel. Only son of the late Xia Tianren, eldest of the four Xia brothers.

Qin An is a former police officer, promoted to local Party Secretary, later replaced by Xia Junting after being demoted to village head. Suffers a brain tumor which leaves him mentally retarded.

Li Shangshan is the silver-tongued treasurer of the village committee charged with the finances of the theatre, has an ongoing affair with the village committee director, Jin Lian.

Li Sanxue is a manager of the brick factory and owner of the fish pond, greedy and aggressive, eventually gets caught having an affair with Wu Lin’s sister-in-law.

Wu Lin is a stuttering tofu maker, married to Hei’e. Hei’e sister, Bei’e, who also lives with them, falls in love Yinsheng after a (literal) tumble in the hay.

Zhao Hongsheng is a self-trained ‘barefoot ‘doctor, who opens a pharmacy in Qingfengjie. His rhyming couplets and calligraphy make him something of a local literatus, although not nearly on the same level as Xia Feng.

Wang Laoshi is a former Shaanxi opera star, famous for her role in the Picking up the Jade Bracelet.

Reader Report

Shaanxi Opera is perhaps Jia Pingwa’s most fully realized novel, coming closest to the Ming and Qing vernacular fiction which the author has repeatedly said he takes inspiration. Like Ruined City, of which Shaanxi Opera could be said to be a sequel, Jia includes copious amounts of poetry, rhyming couplets, folk songs, pop ballads, and — most prominient of all — snatches of famous operas.

To give one example, during the wedding banquet for Xia Feng and Bai Xue, Yinsheng becomes overcome with emotion and suddenly starts singing an aria from the opera Peach Blossom Fan:

Before my eyes, buildings rise

Before my eyes, you welcome our guests

Before my eyes, buildings fall

Completed by the Qing-dynasty dramatist and poet Kong Shangren in 1699, The Peach Blossom Fan gives an account of the downfall of the short-lived Ming dynasty, as told through a tragic love story between a gifted scholar and beautiful courtesan — hardly an auspicious subject to bring up on someone’s wedding day. This sense of impending doom is reinforced by a rhyming couplet pasted on the door, penned by the tone-deaf Zhao Hongsheng:

Without destruction, there is no progress

True feeling comes from conflict

Much like in The Peace Blossom Fan, the ill-fated romance between Xia Feng and Bai Xue provides a narrative thread around which the decline of Qingjiefeng village is built. This decline is presented as both supernatural and mundane in origin, owing to the construction of Route 306, a highway that cuts through the traditional farmlands of the village, reputedly destroying the village’s feng shui. More directly, however, the controversy around the construction of the highway pushes the long-time village head, Xia Tianyi, to organize the villagers in protest. The response of the local authorities is swift and merciless: Xia Tianyi is removed from office and replaced with his eldest nephew, the brash and impulsive Xia Junting.

Despite cutting an impressive figure, Junting’s inexperience allows the local officials to manipulate him into making concessions which will have dire consequences for the village. Acting through the duplicitous, two-timing accountant Shangshan, they convince Junting and his parallel in the Party bureaucracy, Qin An, to allow a nephew of the township illegally log the river dike, irreparably compromising the integrity of the structure and directly sabotaging the former village head’s lifelong efforts to reclaim this area of wasteland. In this way, the external state of the natural environment is shown to mirror the internal state of the character moral landscape.

Thanks to a unique quirk of the Yellow River, whose heavy silt content contributes the building up of high walls of earth on either side of great river, flood control has been a primary concern of Chinese rulers since time immemorial. Indeed, one of the earliest Chinese emperors, Yu the Great, is revered not for his skill on the battlefield, but instead for his mastery of the waterways, through the clever use of irrigation canals and dredging. In Shaanxi Opera, Xia Tianyi is likewise looked up to for his ability not only to subdue the unruly villagers, but also for his willingness to make tough, and often unpopular, decisions on their behalf. While Junting is domineering enough to achieve the former, he is consistently unwilling to sacrificial material comforts for the sake of preserving the village’s autonomy.

This critical moral failing is demonstrated early on in the novel, when Junting negotiates a new electricity contract with the local officials, who extract promises for more money from the village coffers — most of which will doubtless end up in the pockets of the officials. Although appearing on its face to be a novel about a single village, on closer inspection Shaanxi Opera proves to be a biting satire demonstrating the myriad of ways village-level politics can become riddled with petty corruption and gridlocked by ever extravagant favors and gifts.

At the same time, the fate of the protagonist, Yinsheng, is contrasted with Xia Feng, who makes good and becomes a famous writer in the city. In the village and surrounding area, Yinsheng is perhaps the second most famous figure after Xia Feng, but for all the wrong reasons — he’s loud and foul mouthed, and possibly insane. Haunted by visions of his dead father, a village cadre sold out by cold-blooded Shangshan, Yinsheng seems to possess supernatural abilities, recalling things he never heard, and projecting himself into situations he could not possibly have taken part in.

This omniscience, coupled with his unrequited love for Bai Xue, leaves Yinsheng deeply cynical about life in the village. Rather than winning him fame and fortune (as with Xia Feng’s talent for hiding the truth behind a web of pretty words), Yinsheng’s unique talents curse to him to a life of ridicule and isolation. Beyond simply speaking to the general disparity between the urban and rural (or the mundane and supernatural) Jia seems to use the paired characters of Yinsheng and Xia Feng as foils for the two sides of his own personality, adding yet another layer of complexity to the novel.